‘Research/Policy Comment Series – with this brief paper CAIDG is commencing a series of contemporary research and policy commentaries which are meant to inform a wide audience about issues of AI and data governance, particularly in Singapore. The commentaries in the series to follow will be written and presented in a form that is both interesting and accessible for a wide audience keen to know more about policy developments and regulatory challenges posed by the application of AI and the management and use of personal data in particular. We invite questions, comments and considerations about the issues raised in the series, and hope the papers to follow will stimulate constructive public discussion..’

Strengthening measures for safe reopening of activities: ethical ramifications and governance challenges

CAIDG Research Team

Introduction

The Singapore surveillance technology, designed to prevent and control the spread of COVID-19, is soon to be expanded and integrated in an effort to sharpen the tracing and tracking potentials of data use. As a consequence of the intended developments, it will be possible to combine existing technologies, share their data, and get more personalised indications of infection risk. No doubt these are worthy possibilities in the context of health and safety policy.

At the same time, why should these developments raise distrust, impede efficacy and challenge the integrity of personal data? Our research shows two policy variables that will be explored in this brief paper. Intrusive surveillance technologies will challenge trust within the community and dull technological efficacy. Potentials for distrust and the consequent reduction of tech efficacy are exacerbated when data sharing possibilities are built into these policy shifts. Second, if information deficits keep citizens in the dark about these developments and there is no proactive community awareness policy for general public awareness and citizen engagement in monitoring data subject impacts, then trust will diminish both in the tech and its sponsors. Whether this downturn is due to fact or fiction means nothing when uptake is essential for efficacy, and compulsion (direct and implied) will eventually erode confidence to such an extent that the control outcomes for these applications will be muted.

The intentions of the paper are simple, although their resolutions are more complex. In the past, insufficient community awareness and inclusion had retarded app take-up rates and therefore, its efficacy. There is ample evidence that addressing these concerns in policy adaptation is as essential for efficacy as is tech refinement and data consolidation. Like it or not, policy here is the slave of community confidence, and enabling this further is an indication of what follows.

False positives, trust erosion, and damaging efficacy

On 9th September 2020, the Singapore government announced three changes to how it is reconfiguring its contact tracing capabilities. Firstly, from the 14th, the government will be distributing nationwide TraceTogether tokens that work similarly to the TraceTogether app for proximity tracing, and are designed for those who have difficulties uploading the app. Secondly, people using the TraceTogether app will soon be able do a ‘self-check’ to see if they have visited the same venues as COVID-19 cases. Thirdly, the Ministry of Manpower is currently piloting ‘TraceTogether - Safe Entry’ in convergence at selected venues and events. It is interesting that this responsibility has been given to the employment ministry in recognition of what we detail below as distinctly different risk profiles across the workforce.

For a brief recap of how are at this point, here is a timeline of key developments:

- 20 March: Singapore launches TraceTogether mobile app to boost COVID-19 contact tracing efforts (BlueTrace’s White Paper) (Smart Nation press release)

- 9 May: Implementing Safe Entry and Safe Management Practices (MOH, CNA, Smart Nation)

- 13 May: Reopening of the economy will be gradual and in phases (wearable dongles may be introduced)

- 5 June: Enhancements to the TraceTogether Application (Smart Nation Office), Balakrishnan speaking about it

- 7 June: Change.org, Singapore says ‘no’ to wearable devices for COVID-19 contact tracing (change.org petition), ZDNet’s coverage

- 8 June: FactSheet on the TraceTogether Programme (Smart Nation Office), COVID-19 Contact Tracing ‘absolutely essential’ (CNA)

- 9 June: How new token and app will address privacy concerns (ST)

- 15 June: Decision not to use Apple-Google API for Singapore’s Contact Tracing efforts (ST)

- 28 June: Seniors to receive first batch of TraceTogether tokens

- 9 September: (1) Commencement of nation-wide distribution of TraceTogether tokens; (2) Piloting of ‘TT-only SafeEntry’ at selected venues; (3) self-check and SMS service for people to be alerted if they have visited the same venues as COVID-19 cases

The review that follows is intended to raise awareness of these pandemic control developments and highlight the ramifications and governance challenges posed by these new revisions. Consistent with findings in the Centre’s other COVID-19 research dimensions, it is necessary that data subjects and citizens at large be fully informed of new response policies and be included in their implementation and monitoring, if trust is to be sustained, and efficacy facilitated. Our overall advice to policymakers and advocates of these intended developments is to engage in a concerted and targeted public awareness campaign about the nature and consequences of resulting data use, the risks associated with misunderstanding and the accountability and citizen engagement mechanisms in place to address these risks. If this policy development is treated as a genuinely shared exercise between citizens and the state, with pandemic control the essential and definitive purpose, then it is our view that community trust will be advanced and have its efficacy maximised.

1. Self-Check and SMS services: anxiety governance?

In considering the novel impact of these proposed developments, it is useful initially to reflect on the difference between apps used for exposure notification and how they might be activated for contact tracing. The debate world-wide around contact tracing, particularly in its first few months of policy implementation in the jurisdictions with successful roll-out (when the enthusiasm for creation of digital apps was at its peak), concentrated around centralised and decentralised data retention solutions. The central question dividing these two approaches was – why do we need a central database, and what potential harms does this present (e.g. loss of privacy, potential discriminatory consequences for marginalised or disadvantaged communities through the identification of social demographics)? In many of the initial arguments about potential challenges posed, a centralised system was almost always deemed unnecessary and the problems it posed for data integrity were relatively more significant and varied than a fully decentralised system (e.g., a centralised system is more vulnerable to data breaches than would-be decentralised alternatives). Since then, commentators have increasingly recognised that the decentralised system is not the most efficient in fulfilling contact tracing imperatives. As we have seen, the Apple-Google API, which some authorities are currently using as their foundation for development, operates on a decentralised model (i.e., data is stored on the phone of the user) which notifies people if they are exposed to COVID-19-positive individuals. The Apple-Google API, as such, only allows for exposure notification services. Therefore, some details of identification are sacrificed in the decentralised approach in favour of privacy and personal data protection.

On the other hand, TraceTogether has amalgamated the logics of centralisation and decentralisation. Proximity data the app collects stays on the user’s phone until said user tests positive for COVID-19. From there, a code is provided to the user, and their phone’s records are uploaded to a server. This data then complements the manual efforts of contact tracers and exposure notification services.

While this differences between exposure notification and contact tracing may seem inconsequential, we suggest that this distinction remains important. As others have noted, exposure notification apps will most likely “suffer from a high rate of false positives – falsely informing users that they may have been exposed to someone with COVID-19 following situations in which transmissions would likely be highly improbable”. For example, data subjects and infected parties could have been “close” to each other, as defined by Bluetooth signals, but may be physically separated by walls or other transmission barriers. In places where there are multiple impermeable partitions, the false positives end up creating anxiety amongst users who are under the wrong impression that they might have been infected. The result is a reduction in trust in the technology, as well as its state promoters.

Notably, it was this difficulty of identifying meaningful contact, that the TraceTogether development team wrote,

“...we caution against an over-reliance on technology… the experience of Singapore’s contact tracers suggest that contact tracing should remain a human-fronted process. Contact tracing involves an intensive sequence of difficult and anxiety-laden conversations, and it is the role of a contact tracer to explain how close a contact might have been exposed - while respecting patient privacy - and provide assurance and guidance on next steps... [This approach helps] to minimise unnecessary anxiety and unproductive panic. These are considerations that an automated algorithm may have difficulty explaining to worried users.”

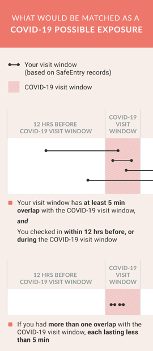

What does this mean for TraceTogether’s newly proposed Self-Check service? As mentioned previously, TraceTogether functions as a complement to manual contact tracing efforts: it means users do not have to limit the indications of infection to third party notification by contact tracers, or if they start to exhibit symptoms. The ‘self-check service’ has essentially added the exposure notification functionality to manual contact tracing efforts. According to TraceTogether developers, a user needs to have a minimum overlap of at least 5 minutes with a COVID-19 case or have their phone pinged with a confirmed case more than once, before receiving a notification that such user has been exposed.

Source: How are my possible exposures determined?

Previously, to verify one’s exposure to the virus, users would match their TraceTogether log against MOH’s updates of confirmed COVID-19 venues. The new automated process will effectively remove this step and make it easier for users to check if their activities and movement have exposed them to the virus.

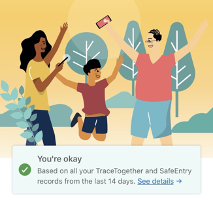

This notification service, together with more conventional tracing efforts, effectively widens the pool of individuals who may be driven by their concerns and anxiety (of potentially having caught the virus) to self-report to the nearest testing centres. In the past, a user may only have gone for a swab test if they started exhibited symptoms, or if they were contacted by MOH; now either the user is “okay” by the app’s standards, or they have been “exposed” and should take precautions, or they might be at a relatively higher risk of COVID-19 if they have been contacted by contact tracers. This combined approach provides additional levels of risk evaluation and adds some degree of self-determination to the decisions that a citizen take with regards to precautionary measures.

TraceTogether home screen

The question can then be understood and put forth by a concerned citizen as such: is the addition of this exposure notification functionality necessary and warranted? From the image above, the criteria for what constitutes a possible exposure appears to be casting the widest possible net: if the user was in a NTUC supermarket and paused to think about what brand of noodles to buy, or if the user stopped to reply to an email and inadvertently stood “near” (as defined by TraceTogether) a soon-to-be confirmed COVID-19 case, they would have be “exposed”, even if said case was standing in an opposite aisle. This is should not qualify as a meaningful encounter. If such situations led to notifications of more false positives, rather than only increasing the rate of positive notifications, these efforts would then only serve to exacerbate user’s anxiety exacerbation and reduce their trust in the app and the control mechanisms.

The whole point – arguably, the advantage – of Singapore’s contact tracing system so far has been that its “human in the loop” commitment has reduced uncertainty and anxiety of exposure and infection through the identification of meaningful contact between positive patients and their networks. The negative consequences from false positives are less likely to affect certain classes of workers – i.e. those stably employed, working from home, and those who work on a flexible schedule, and hence, are able to isolate themselves away from others and get tested with little repercussions to their economic well-being. On the other hand, for workers who are engaged in high-contact jobs, or employed in more precarious labour situations, this flexibility of option may not be as easily available and therefore anxiety over false positives will take on a discriminatory character. Workers who are more likely to receive multiple false positives through an over-active exposure notification system, will then be forced to more detailed and worrying monitoring of physical symptoms, and to left to decide whether they ought to self-isolate from their family members and housemates over each two-week incubation period with obvious socioeconomic consequences.

The convenience derived from this development and the public health benefit of quick identification, complemented with access to testing facilities is obvious (recognizing also that the ramped-up testing centres in Singapore allow for an increased number of people to have a choice of getting tested quickly and with less fuss). Nonetheless these exposure notification messages may produce more confusion and anxiety within an already unsettling time, where trust in control responses is fragile. These notifications also risk worsening the existing COVID-19 fatigue, which may result in increased frustration with the entire digital contact tracing system. In a survey commissioned by The Straits Times on 16th August 2020, 44 per cent of Singaporeans already expressed their dissatisfaction with the number of measures imposed to limit the spread of the virus.

Against the background of our research into citizen disquiet stemming from pandemic control responses, we wish to emphasise the importance of reducing citizens’ anxiety in the process of technologizing COVID control. Our research has found that what the state originally designed as health control measures may have anxiety-exacerbating side-effects that go well beyond the natural or expected consequences of virus reduction. Such anxiety not only endangers trust and efficacy but clouds the central critical issues of concern that arise out of surveillance and mass data-sharing. These negative reactions must be adequately addressed. The successful correction of these worries can result in less debates surrounding future control responses and a smoother implementation process.

Additionally, there is also a fundamental lack of empirical data supporting the legitimate control potentials of these new updates. The benefits and risks of these upcoming measures are not yet broadcasted, and insufficient access to such details is burdensome to data subjects who are increasingly asked to place their uninformed trust in the State. The release of such empirical, supportive data would go a long way towards promoting transparency, citizen inclusion, and public trust. It is important that the sponsors of new technological intrusions learn from past mistakes and avoid information deficits leading to suspicion and the withdrawing of confidence which has a negative impact on what the new tech is trying to achieve.

2. TraceTogether-only SafeEntry Check-In: proximity and geolocation data all in one

According to the new updates,

“To facilitate contact tracing efforts, MOM will be piloting the deployment of SafeEntry that requires the use of either the TT app or token to check in at selected venues, to facilitate the further easing of measures at these settings.

This ‘TT-only SafeEntry’ will first be piloted at selected venues, and will be expanded over time along with the introduction of the national distribution exercise. This could include venues where there may be larger groups coming together, particularly where there is close interaction among attendees, or where masks may not be worn at all times due to the nature of the activities. Supplementing SafeEntry with proximity data from TT can enhance safety for participants. This was trialed at the first MICE event held at the end of August, with more pilots starting progressively from September 2020.”

According to the government, this development might reduce contact tracing from 4 to 2 days. For instance, if Jane Doe attended a conference with 25 people in the room and found out afterwards that she is infected with COVID-19, the people sitting closer to Jane have a higher risk of getting the virus. However, these conclusions depend on the nature of the event and its population and internal location. For example, do attendees move around a lot? Were people seated in a socially distanced manner? Was everyone masked?

In examining the dynamics of further data sharing, we start with the moment that SafeEntry is activated. Contact tracing in Singapore is digitally supplemented by two systems: both TraceTogether (TT) and SafeEntry. By piloting TT-mandated SafeEntry check-ins at specific events and venues, this system creates environments of identified activity. The data subject is identified through the registration of their NRIC number and so the apps combine to transmit identified data to the centralised database about who is where, when and for how long. Such identified data is beyond any privacy-preserving aspect of TraceTogether. It seems that the intention of combining TT data and SafeEntry data for larger associations in conferences and entertainment events is to make the data capture more three dimensional. TT gives data on association and Safe Entry locates and identifies the data subject in a richer interactive space. Temporal and spatial data is much more detailed and potentially intrusive as a result

Both these apps originated with different purposes and have different approaches to privacy. TraceTogether is privacy preserving insofar as it does not reveal your physical location but works to record proximity with another phone (with TT installed) via Bluetooth technology. SafeEntry is linked to the data subjects’ NRIC number and therefore privacy protections can only be considered at the storage end of the data chain.

By combining TraceTogether (association data) with SafeEntry (location data), the government is now privy to a more specific (and previously unknown) type of information/data that is:

- Who is person X meeting (as may be revealed by the Bluetooth proximity data in the TraceTogether application) and

- Where is X meeting Y (as may be revealed by the SafeEntry application)

Previously, the government was only able to conclude that X and Y checked in to building Z with SafeEntry. They cannot verify with sufficient certainty that X and Y are associated or, are in “close contact” (save for assuming their relationship by examining the time that both individuals checked in or out of the building).

The new measures seek to combine both TraceTogether and SafeEntry datasets. Therefore, one’s privacy is further eroded as the State is in a position to determine (where it is allowed to) who person X was in contact with, and where X and Y met.

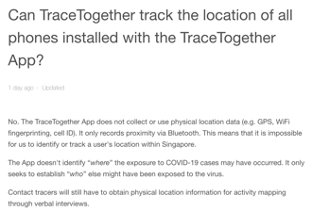

Source: TraceTogether, screenshot taken 10th September 2020

For now, TraceTogether remains explicitly an app that “does not collect or use physical location data”. With the move towards TT-only SafeEntry check-ins, more might be done to communicate that the combination of both apps does in fact, allow for association-related information to be gleaned easily. With transparency in mind, it is worth questioning why the information contained in the above screenshot has no mention of SafeEntry at all. While it could be argued that TT does not do check-ins and only uses Bluetooth to indicate proximity, the new function offered by using TT to activate SafeEntry combines both functions. The intention for the TT/SafeEntry consolidation is that in certain settings, it will be compulsory for the data subject to have TT (either the token or the app) in order to fulfil SafeEntry requirements. In that way, the compulsion attached to SafeEntry will spill over to the uptake and usage of TraceTogether, further complicating the data harvesting picture.

It could be argued that we are moving towards mandating the use of TraceTogether (be it through the app or the token) without the government explicitly conceding so. This is a further cause for concern, seeing as SafeEntry is already mandated. Although it is not possible to access premises in Singapore with QR code entry unless the citizen complies with SafeEntry, there is a vestige of choice in that the citizen can choose not to enter said premises. While certain users feel greater autonomy in using SafeEntry (in deciding where they visit, and hence the kinds of location data they give to the state), they are often constrained in premises like schools and hospitals, where any such choice is nominal.

Until now, whether a data subject uploads TraceTogether is a matter of self-determination, unless and until they have tested positive. Designating that certain large-scale events can only be accessed through the use of TT/SafeEntry combinations will challenge the issue of citizen determination even further, and without a candid discussion in the policy arena concerning these potentials, trust will be a casualty.

As island-wide distribution commences of TT tokens which act to combine TT and SafeEntry, and we move increasingly towards wider TraceTogether usage, we may also finally reach the critical mass required for digital contract tracing to work optimally. Already, it is not possible to enter malls and grocery stores without SafeEntry. As the nation-wide distribution of tokens commences, it is not inconceivable that TT-only SafeEntry check-ins can be expanded to encompass a wide variety of mundane, daily access options as well. The press release cited above has been vague about this potential enlargement and qualifies a hard-line decision from the government against making Trace Together mandatory.

The apparently provident distribution of TT tokens is intended to remedy the low uptake of the app, and improve tracing efforts by ensuring that children and the elderly are part of the TraceTogether programme, so as to improve tracing efforts. However, absent of adequately addressing the issue of citizen self-determination and showing the app has been essential and helpful with more in-depth descriptions and statistics, the nation-wide roll-out of tokens relies on moralising impetus to use them rather than a convincing evidenced-based argument. The choice to not use TraceTogether - whether motivated by doubt of the app’s efficacy or distrust of how data is being collected and used by the government, or even concerns about its technical inconvenience - may potentially be silenced, and instead repackaged as a failure of one’s responsibility to others: “Why, given that you have been given a token, are you refusing to use it?”

This moralising impetus, together with what might result from the new “exposure notification” function, connects back to the earlier-expressed concerns about heightened anxiety through multiple exposure notifications and the eventual disillusionment with digital apps. It cannot be assumed that the ends (of promoting public health) should always justify the means – privacy risks must first be acknowledged, and citizens’ trust must be earned.

When the TT-mandated Safe Entry initiative was first announced, the public was informed that the initiative would only be mandated at certain “designated venues”. That is to say, outside of these venues, residents are not required to “connect” to Tracetogether when activating SafeEntry. Put differently, if one had earlier checked in on the TraceTogether application, they are at liberty to “disconnect” from the application (by turning off their Bluetooth) after leaving the venue.

However, what was not made apparent to the public in the explanatory advice accompanying the government’s strategic announcement that “free TraceTogether tokens would be supplied to anyone who wants one”, is the significant condition of use that these tokens cannot be switched off and have a battery life of approximately 6 months. Whether this is a deliberate feature or a design flaw of the token – it is inconsistent with accountable/explainable policy development if residents are not made aware of this condition of use.

This option to “disconnect” from TraceTogether remains available for users of the mobile application. Arguably then, this application may be viewed as more privacy-preserving than the token. The associated lack of disclosure could diminish good will in the State and represent a genuine challenge to citizens’ self-determination. Public trust in the State’s power, authority and legitimacy when coordination pandemic prevention and control, would also be affected.

3. Privacy Pragmatics

In a practical sense, it is presently possible for the government to share data from TraceTogether and SafeEntry and to identify TT data subjects. With SafeEntry, the government knows and will continue to know data subject’s location based on the collected data. However, once the citizen checks out, is not possible to determine their location, except through proximity tracing and TT.

SafeEntry data is identifiable through its cross reference to the NRIC number of the phone user. Provided that the data subject/phone user is one and the same (as the apps assume) and their identity corresponds with the NRIC details stored on the SafeEntry app, then it would not be difficult to cross reference the TT and SafeEntry phone numbers with the NRIC details on SafeEntry and share identified data from both. However, any data sharing without the knowledge of the data subject would clearly infringe the ‘voluntary spirit of TraceTogether’. That said, there is no indication that the government is acting in this fashion and there has been no notification on the TT conditions of use that this is envisaged.

Currently, the government indicates that it only uses TT data when the data subject is identified as a confirmed case and/or if users are contacted by the government for having been in close proximity contact with a confirmed case. When a person is contacted by MOH, they are “required by law to assist in the activity mapping of their movements”. If a confirmed case does not use TT, the contact tracing process is not an easy task given that SafeEntry data does not provide data related to close proximity. If a citizen becomes a confirmed case confirmed and they are a TT user, the government will use both sources of information (SafeEntry-location and TT-proximity), with MOH contacting the person and notify them of the risk status consequences.

Therefore, if both datasets have always been available to the government and this combination of SafeEntry/TT is merely confirming sharing potentials, then the issue is not necessarily that one’s privacy is eroded but the trajectory of how the challenge to identified data privacy eventuated:

-

- The ideal of wanting to be privacy preserving (stated in the TT policy) and also maximally effective at contact tracing by using digital technologies, seems to necessitate some privacy trade-offs. We do not hold that this is inevitable, as there being examples of privacy protecting tracing apps which have very high up-take and therefore, high efficacy levels.

- Without trust in data integrity, the reality that the public uptake of TT remains low, which then has led to further reliance on SafeEntry for both crowd control and contact tracing, with the public has increasingly accustomed to using SafeEntry.

- This digital infrastructure has been (arguably unintentionally) structured in such a way that the government then has the option of combining both sets to enhance contact tracing measures.

Since both datasets are with the government in centralised storage, the concern is not only potential erosion of people’s privacy, but that the announcement of TT/SafeEntry combinations was made without explicitly acknowledging that doing this dampens the privacy-preserving aspect of TraceTogether. Even though TT as an app is seemingly designed to work with minimal data, which makes it difficult to reproduce social graphs of one’s interactions, the TT/SafeEntry combination changes this capacity because of the granularity offered by merging and sharing both datasets (as mentioned earlier). In the pre-existing arrangement, it was not possible to know one’s geo-location based on TraceTogether, and with SafeEntry, it was also not possible to know close proximity data. While TraceTogether and SafeEntry may be combined, this does not automatically mean that TT allows the government to see geo-location with that data from TraceTogether itself, but through SafeEntry’s geo-location data. The privacy issue therefore does not simply reside in either application, but that through possible identification and data sharing which the merged facility enables.

Originally, the choice whether to use TT (upload, or turn it off/on) resided with each citizen and that had formed the ultimate privacy protection. That possibility is being limited now. Privacy concerns are exacerbated through the limiting of self-determination and this may impact on trust, and efficacy for the response portfolio at large.

We return specific forms of transparency that should govern developments in surveillance policy and influence citizen trust in the positive. Our broad argument is that policymakers need to build citizen’s trust rather than to continuously assume that such trust exists within provident state policy initiatives. It would have been preferable in our view for policymakers to have first carried out impact assessments focusing specifically on data integrity and citizen trust. If the legitimate motivation for the new policy approach is to ensure the safety of major events in Singapore, with the social and economic benefits of opening up these potentials represent, then the negative consequences for personal privacy, data integrity, and self-determination could be argued in balance.

Privacy concerns here have relevance in terms of the data sharing because of the compromise of self-determination and the capacity for identification. Presently, the data subject agrees (or not) to use TT and in lesser ways, SafeEntry. With the TT/SafeEntry combination facilitated through a token device that cannot be deactivated, such self-determination is minimal. The challenge here is not a pragmatic acceptance of data sharing by the state in any case but citizen consent and acknowledgement of compulsion, which are absent and unaddressed.

4. Partnership between the public and private sector: governance and accountability potential issues

According to the Ministry of Health’s website, the Government is also “working with the private sector who are interested in supplying contact tracing tokens to companies, to ensure that these Tokens and the national TraceTogether Token can mutually detect one another and contribute to a unified contact tracing ecosystem.”

However, nothing has been explained about these private-public partnerships and how will they will work in practice. From an accountability and governance perspective, many issues could be provoked by this statement. Firstly, in jurisdictions such as Singapore, the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) generally does not apply to “any public agency or an organisation in the course of acting on behalf of a public agency in relation to the collection, use or disclosure of the personal data”. Consequently, the various obligations under the PDPA relating to consent, purpose limitation, notification, access and correction, accuracy, protection, retention limitation, transfer limitation, etc. do not apply to public agencies and private companies that are working in the project with the Government. Additionally, the boundaries of accountability for these private companies have not been explained to the public, even though it was already announced that both sector are working together in the so-called “unified contact tracing ecosystem”.

With the pandemic regulation of the migrant worker population, it is quite apparent the Government has enlisted the help of the private sector (including dormitory operators and the employers of migrants) with “policing powers” to deal with pandemic containment. The governance consequences of this divesting of regulatory responsibility could potentially be problematic, owing to the lack of democratic review processes, public accountability mechanisms, and potential for abuse by vested commercial interests.

5. Necessity and Expiration

Singapore managed to keep its infection rates low within the community despite the voluntary nature and low uptake of the digital tracing measures. This was all done even without TraceTogether. The availability and existence of these technologies should not be enough to mandate their combination and adoption without scrutiny, transparent disclosure of how they work, in practice and open monitoring of the consequences of their use to the satisfaction of data subjects.

The more data that is collected and/or “merged” – the higher the probability of a potential data breach. This risk might be even more significant if we consider the announced collaboration with private companies (with differential protective regimes and varied privacy practices) in the “unified contact tracing ecosystem.” Additionally, due to the inapplicability of the PDPA to the public sector, it is not clear which mechanisms hold the public sector accountable for potential data breaches and which authority is in charge of overseeing these developments. There are recent historical precedents for just such concerns. Singaporeans’ data have been exposed in previous data leaks (e.g. HIV data leak, SingHealth data leak), and these breaches should be considered as ample justification for strongly promoting and prioritising data minimization.

Further, our freedom to enter into “phase 3” is spoken about by authorities as conditional on our acceptance of more control measures that may paradoxically, further intrude into civil liberties. With the aim of maintaining safety, increasing surveillance regimes as infection rates drop may further confuse community understanding of what should constitute “the end of an emergency” and when the appropriate decommission the State’s control measures will occur. The claim that these control technologies can help to “facilitate future relaxations” can be used ad infinitum to heighten, justify, and normalize surveillance. Such considerations of temporary trade-offs in civil liberties for community health/safety outcomes (an argument which still requires empirical substantiation) is just the type of reflection that requires public awareness and community consultation campaigning.

Last updated on 16 Oct 2020 .